Site Search

Search within product

第744号 2022(R04).10発行

Click here for PDF version

§被覆肥料に由来するマイクロプラスチックの生態リスクと排出量

National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences

上級研究員 永井 孝志

§中華めん用小麦「ラー麦」において高い子実タンパク質含有率を確保できる省力施肥法

Fukuoka Prefecture Iizuka Agriculture and Forestry Office

Iizuka Extension Guidance Center

石丸 知道

No § Soil - No. 15

化学肥料だけしか使わない畑のコムギの生育

−堆肥だけの畑と比べる−

Jcam Agri Co.

北海道支店 技術顧問

松中 照夫

Ecological risk and emissions of microplastics from coated fertilizers

National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences

上級研究員 永井 孝志

Introduction

マイクロプラスチックは,5mm以下のプラスチック(化学繊維やゴムも含む)と定義され,一次マイクロプラスチック(最初から5mm以下の粒子として製造されたもの)と二次マイクロプラスチック(製造後に環境中などで破砕・細片化されたもの)に大きく分類される。これらは世界中の海洋においてその存在が確認されており,そこに生息するクジラやウミガメ,海鳥,魚などの様々な生物の消化器からも検出されている。このため,マイクロプラスチックの人の健康や生態系への影響について現在注目が集まっている1)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

2015年に米国で化粧品に配合された洗顔スクラブなどのマイクロプラスチックビーズが規制されたことを皮切りに,各国でも規制が始まっている。これは,環境中で分解できず回収困難であることが主な理由であり,実際の環境中で悪影響を与えていることが証明されたからではない2)。日本でも2020年7月からレジ袋の有料化が始まるなどの取り組みが進んできた。

農業用途で使用される被覆肥料は,肥料成分が数mmのカプセルに入っており,カプセルから徐々に肥料成分が溶け出してくるものである。長期的に効き目があり,施肥の省力化や施肥量の削減,肥料成分の水系への流出防止に有効とされている。ところが,その小ささから一次マイクロプラスチックとしてのカプセルの回収が困難であり,水系に流出したものが多数見つかっている3)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

Therefore, the purpose of this article is to summarize the problem of runoff of plastic capsules of coated fertilizers into water systems in terms of ecological risk and emissions.

2. ecological risk from microplastics

Ecological risks from microplastics can be divided into three types

(1) Hazardousness of plastic particles themselves

(2) Toxicity due to various chemicals added to plastics

(iii) Persistent in the environment adsorbed on plastic particles

機汚染物質による有害性粒子毒性に関してBurnsら(2018)は,2018年までの毒性評価や環境中濃度の研究報告を網羅的にレビューし,現状のマイクロプラスチックは水域生態系に影響を示す濃度レベルではないと報告した4)。この論文中では,文献から収集した多数の水生生物に対する無影響濃度を用いて,種の感受性分布という手法(濃度と影響を受ける種の割合の関係を確率分布で表現する) 5)により,生態系に対する予測無影響濃度を粒子サイズごとに見積もった。実際の環境中におけるマイクロプラスチックの濃度分布は予測無影響濃度よりも数桁低いところにあり,現状生態リスクは懸念レベルにないと評価された。

また,プラスチック製品には可塑剤や紫外線吸収剤,酸化防止剤,剥離剤,難燃剤など様々な添加剤が配合されている。プラスチック自体は消化管から体内へは吸収されずにほとんどが体外へ排出されるが,添加・吸着している化学物質は体内に吸収される。このような化学物質を添加したマイクロプラスチックを魚などに曝露させると,肝機能障害や腫瘍の発生などの影響が見られた。ただし,これは実際の環境中濃度よりも一桁以上高い濃度条件で見られた影響である1)。さらに,マイクロプラスチックへの吸着が問題となっている疎水性有機化学物質については,海洋においてプラスチックに付着している割合は非常に低く,現時点で実質的に生態リスクの懸念につながる可能性は低いと整理されている6)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

欧州委員会の政策のための科学的助言コンソーシアムも,生態リスクは現状では懸念レベルにないことを報告している7)。ただし,マイクロプラスチックの環境への排出量が今後も継続した場合,100年以内にマイクロプラスチックの生態リスクが広範囲で顕在化する可能性があるとも述べられている。

From the above, it can be summarized that the ecological risk of microplastics is currently below the level of concern, but that they should not be continuously discharged any more. However, while it is true that "harmful effects were observed when organisms were exposed to microplastics (at concentrations much higher than the actual environmental concentration)" and "microplastics were detected in the environment or in the bodies of organisms (but at concentrations much lower than the no-effect concentration)," the image of microplastics would change greatly if this information were spread in a form that omits the parentheses. However, if this information is spread in a form that omits the parentheses, the image will change significantly.

また,マイクロプラスチックの生態リスク評価の残された課題としては以下の点が指摘されている6)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

● サイズ,形状(球体・ファイバー・フラグメント) ,ポリマータイプ(ポリスチレン・ポリエチレン等) ,経年劣化の有無等による毒性への影響

Should the unit of concentration be weight or number of particles?

No. of uptake into the body

Comparison with natural particulates

3. sources and emissions of microplastics

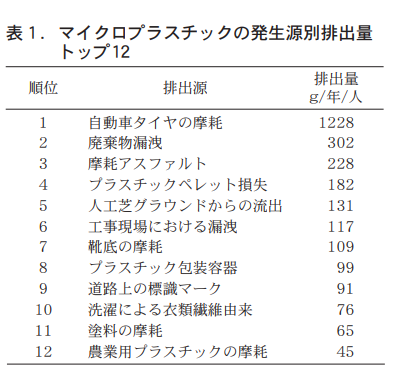

マイクロプラスチックの発生源としてはペットボトルやレジ袋,被覆肥料カプセル,人工芝などが注目されがちであるが,発生源の全体像はあまり知られていない。ドイツのフラウンホーファー研究所による報告では,発生源をトップ30までリスト化している(表1ではトップ12までを示す) 8)。これを見ると全体の排出量は2,500g/年/人程度となっている。このうち排出量が多いのは摩耗などで発生する二次マイクロプラスチックであり,一次マイクロプラスチックはマイナーな発生量となっていることがわかる。

さらに二次マイクロプラスチックの中でも,タイヤ・アスファルト・靴・人工芝などの摩耗が非常に多い。また,12位に「農業用プラスチックの摩耗」というカテゴリがあり,これは農業用途の全てが含まれると推測される。欧州においても被覆肥料が使用されるものの,水田が少ないため水系への流出は日本よりかなり少ないと考えられる。よってこのカテゴリの排出はビニールハウスやマルチなどの大きな資材の摩耗によるものと推測される。

次に,農業由来のプラスチック排出について整理する。農業分野から排出されるプラスチックは,農業用ハウスやトンネルの被覆資材,マルチ,苗や花のポットなどに加えて,被覆肥料のカプセルがある。農林水産省の資料9)によると,2018年ベースで合計106,501tのプラスチックが排出されている。これらの排出量は環境中に全部出ていくわけではなく,廃棄物としてほとんどのものが処理されている。再生処置・埋立処理・焼却処理のうち,再生処理が7割を超えている。

Looking at the emissions of agriculture-derived plastics by material, vinyl chloride used for plastic greenhouses and polyolefins (e.g., polyethylene) used for tunnels, mulch, and solid coverings account for the majority. The amount of covered fertilizers, along with seedling trays and pots, is classified as "other plastics," and accounts for 171 TP3T (17,928 tons) of the total. The overall amount of emissions has been on a decreasing trend.

「その他プラスチック」の内訳で被覆肥料のものがどれくらいかの記載がないため,ここでは簡易に推定を試みる。まず,「その他プラスチック」の排出量17,928tを日本の人口で割ると140g/年/人になる。これを,非常にざっくりと育苗トレイ,ポット,肥料カプセルの3つに等分割すれば,47g/年/人という計算になる。さらに,使用された肥料カプセルの10%が水系に流出すると仮定すると,5g/年/人程度となるだろう。農林水産省の別の調査9)によると,施用した肥料由来カプセルのうちの2〜9%が系外に流出し,ほとんどが代かき後の流出だったことが示されている。よって,環境への流出率10%は若干大きめに見積もった値となっている。

さらにマイクロプラスチックの実測調査からの推定値も参照できる。一般社団法人ピリカはマイクロプラスチックの大規模な調査を継続的に行っており,データも公開されている11)。2020年度版のデータからは,マイクロプラスチックの排出量の見積もりが157tでそのうち肥料カプセルが15%つまり,24tとなっている。これを同様に人口で割れば0.2g/年/人と計算される。全体で157tというのはかなり少ない数字であるが,タイヤ摩耗塵などの小さすぎる粒子はカウントされていないと考えられる。

From the above, it is estimated that the actual emissions are between 0.2 and 5 g/person/year. Assuming that the total emission of microplastics in Germany is 2,500 g/person/year and the same in Japan, the emission from coated fertilizers is estimated to be less than 11 TP3T of the total. Even if the emissions are limited to agricultural plastics (Table 1), the emissions from other sources than coated fertilizers are higher.

4. the nature of the problem with coated fertilizer capsules is not so much a risk issue as it is a garbage issue

Considering that the current ecological risk is below the level of concern and that coated fertilizers are a minor source of microplastic emissions, as we have summarized, discontinuing the use of coated fertilizers as a microplastic risk reduction measure would be very inefficient. If the use of coated fertilizer is discontinued and repeated fertilizer application is considered, it is necessary to consider that fertilizer efficiency will be reduced and the amount of fertilizer dropped will increase, and that repeated field trips for fertilizer application will increase other risks due to vehicle use (tire wear is a top source of microplastic emissions). . Increased fertilizer drops can also cause other environmental problems, such as eutrophication of water systems and greenhouse gas emissions from denitrification. Thus, discontinuing the use of plastics alone will not solve the problem.

So, can we continue to use coated fertilizers without any problems? This question must be considered separately from the issue of risk. Just as it is very unpleasant to see a lot of plastic trash washed up on the beach, capsules derived from coated fertilizers found in large numbers in water systems have an intuitively negative image (they are identified as bad). Then comes the perception that if something is bad, it must have high risk and low benefit. When information such as the negative effects of microplastics comes in, it reinforces their intuitive negative image and they strongly recognize that their intuition was not wrong. In other words, we should not consider that we have a negative image because of the risk, but rather that our intuitive negative image, which has existed from the beginning, is amplified by the risk information.

このため,現状の生態リスクは懸念レベル以下,という情報の提供だけではネガティブイメージの払拭にはあまり大きな効果がないかもしれない。このように,対象を良いか悪いか(好きか嫌いか)という感情でまず判断を下し,その対象のリスクやベネフィットを後付けで判断する,という思考過程を(感情)ヒューリスティックと呼ぶ12)。このような市民の感情や価値観も決して無視するべきではない。

すなわち,リスクがないからごみをその辺に捨てても良い,というわけではないため,水管理を徹底して圃場系外への流出を防止したり,排水口でなるべく回収の努力をしたりするなど,使う側の責任をきちんと負うことにまず取り組むべきである。つまりはリスクの問題というよりもプラスチックごみ問題として考える必要がある。水管理による流出防止対策は,プラスチックだけではなく農薬や肥料成分についても系外への流出を防げるため,全体的に環境負荷が低減する。水田での代かき後の流出量が多いが,排水口での捕集が有効であることも報告されている9)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

In 2022, JA Zen-Noh and industry associations released a "Policy for Efforts to Prevent Marine Discharge of Plastic Coated Shells of Slow-release Fertilizers". The policy outlines the following three initiatives to be achieved by 2030:

(1) Publicize the presence of plastic in coated fertilizers

(2) Implementation of measures to control runoff of plastic-coated shells from agricultural land

(iii) Realization of agriculture that does not rely on plastic coating through the development and diffusion of new technologies

以上のような取り組みに加えて,関係者間での情報共有や,対話や意見交換を通じた相互理解・信頼関係の構築を行うリスクコミュニケーションが求められるだろう。これは一方的な情報提供ではなく,双方向的コミュニケーションが重要であり,説得のための技法という認識を持たないように注意が必要である12)The following is a list of the most common problems with the "C" in the "C" column.

References

1)日本学術会議.提言

「マイクロプラスチックによる水環境汚染の生態・

健康影響研究の必要性とプラスチックのガバナンス」(2020)

2)国立研究開発法人科学技術振興機構 研究開発戦略センター

環境・エネルギーユニット.俯瞰ワークショップ報告書

「社会および産業争力を支える基盤としての環境リスク評価研究」(2020)

3)池貝隆宏,三島聡子,菊池宏海,難波あゆみ,小林幸文.

相模湾沿岸域のマイクロプラスチック漂着特性.

神奈川県環境科学センター研究報告.41, p.1−10 (2018)

4)Burns EE, Boxall ABA. Microplastics in the aquatic environment: Evidence for or against adverse impacts and major knowledge gaps.

Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.37, p.2776−2796 (2018)

5)国立研究開発法人農業環境技術研究所.

【技術マニュアル】農薬の生態リスク評価のための種の感受性分布解析 Ver. 1.0 (2016)

6)岩崎雄一,眞野浩行,林彬勒,内藤航.

マイクロプラスチックの水生生物への粒子影響に着目した有害性評価の現状と課題.

環境毒性学会誌.24, p.53−61 (2021)

7)Science Advice for Policy by European Academies.

A scientific perspective on microplastics in nature and society (2019)

(8) Fraunhofer Institute for Environmental, Safety and Energy Technology UMSICHT.

Kunststoffe in der umwelt: mikro- und makroplastik (2018)

9)農林水産省農産局園芸作物課.

農業分野から排出されるプラスチックをめぐる情勢 (2022)

(10) Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Survey on plastic-coated fertilizers in FY2020 (2021).

(11) PIRICA. Microplastic Runoff Status Database.

(12) Kinoshita, Tomio. Philosophy and Technology of Risk Communication. Nakanishiya Publishing (2016)

In "Ra-mugi" wheat for Chinese noodles

高い子実タンパク質含有率を確保できる省力施肥法

Fukuoka Prefecture Iizuka Agriculture and Forestry Office

Iizuka Extension Guidance Center

石丸 知道

Introduction

The area of Chinese wheat "Ra-mugi" (variety name: Chikushi W2) bred in Fukuoka Prefecture for Chinese noodles is 1,890 ha in the 2020 sowing, accounting for 121 TP3T of the wheat crop area in Fukuoka Prefecture. In order to maintain good suitability for ramen noodle making, the customers demand a seedling protein content of 12% or higher for the planting of "Ra-mugi" (Furusho et al. 2013). In order to secure a seedling protein content of 121 TP3T or higher, Fukuoka Prefecture has adopted a three-fertilizer system, consisting of a bimetallic fertilizer, an ear fertilizer, and an additional fertilizer at the time of ear-justification.

However, since fertilizer application during the ear-justification period is a heavy workload for growers, a labor-saving system was desired (Tanaka 2013). Therefore, we investigated a one-time fertilizer application system in which a combination of a fast-acting fertilizer and a controlled-release fertilizer is applied at the same time of the full-season fertilizer application, thereby eliminating both the ear fertilizer application and the full-season fertilizer application. The controlled-release fertilizers were a 20-day type, which has the shortest leaching period for early nitrogen leaching, and a sigmoid type, which suppresses nitrogen leaching until the stem-planting stage and leaches nitrogen from around the stem-planting stage to the ear-planting stage. S20) was selected. Since nitrogen leaching of coated fertilizers depends on temperature, the leaching pattern may vary from year to year, so the hydrolysis type Kumiai Good IB Granules 33 (J-Cam Agri Co., Ltd., hereafter IB) was also considered. Here, a brief outline of the study is presented.

2. Methods

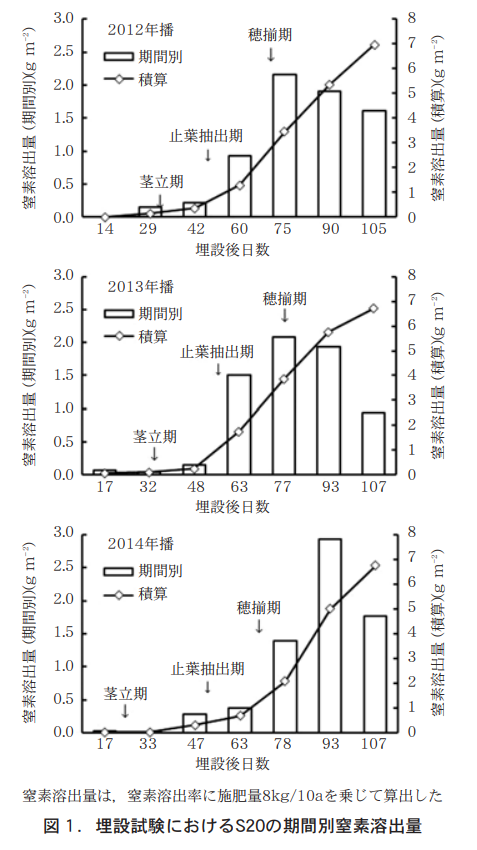

1. Nitrogen leaching by period for S20

S20の期間別窒素溶出量を推定するため,福岡県農林業総合試験場豊前分場(福岡県行橋市)の水田圃場(埴壌土,水稲後作)で,2012〜2014年(播種年,以下同じ)の3か年間,埋設試験を行った。S20を分げつ肥施用時(2012年播は1月31日,2013年播と2014年播は1月28日)に地表面に設置後,地域慣行で行われている土入れ作業を再現するため覆土し,概ね15日ごとに回収した。回収したS20は,PDAB発色法の吸光光度法により残存窒素量を求めた。それぞれの残存窒素量から窒素溶出率を算出し,施肥窒素量を8kg/10aとした場合の窒素溶出量に換算した。さらに,前回調査時の窒素溶出量を差し引いて,期間別の窒素溶出量を算出した。

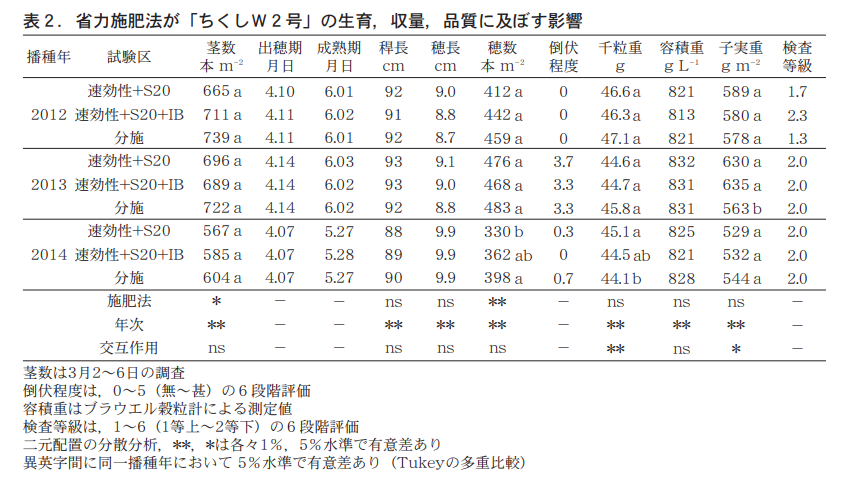

2. growth and yield of "Ra wheat" by labor-saving fertilization

「ラー麦」を供試し,2012〜2014年播で前述の埋設試験と同一圃場で栽培試験を実施した。播種方法は畦幅150cmの4条の条播で,目標出芽本数を150本/㎡とした。試験の規模は1区8.3㎡の3反復で,11月21〜22日に播種した。試験区の構成を表1に示した。基肥は,全区速効性の化成肥料を窒素,リン酸,カリの成分でそれぞれ5,5,5kg/10aとした。省力施肥区は,分げつ肥(分げつ期,1月下旬)施用時に,速効性肥料で3,0,3kg/10aとS20で9,0,0kg/10aの配合肥料,あるいは速効性肥料で3,0,3kg/10aとS20で8,0,0kg/10aおよびIB(33−0−0)で1,0,0kg/10aの配合肥料を施用した。

The amount of nitrogen in the fertilizer blends was increased by 2 kg/10a to a total of 7 kg/10a of nitrogen fertilizer, which was the combined amount of the divided application of ear fertilizer and the full-rotation fertilizer, and the amount of fast-acting fertilizer in the divided application was reduced by 1 kg/10a. In the divided application area, fast-acting fertilizers were applied at 4,0,4 kg/10a as additional fertilizer, 2,0,2 kg/10a as ear fertilizer (applied in early March at the stem-rotation stage), and 5,0,0 kg/10a of ammonium sulfate as additional fertilizer at the ear-rotation stage, based on Fukuoka Prefecture's fertilization standards.

3. results

1. Nitrogen leaching by period for S20

Figure 1 shows the nitrogen leaching rate of S20 buried in late January (at the time of fertilizer application). After 45 days after burial, the total nitrogen leaching rate of S20 was 0.92-1.51 kg/10a from 45 to 60 days after burial (internode elongation stage to leaf stop extraction stage), 2.09-2.17 kg/10a from 60 to 75 days after burial (leaf stop extraction stage to flowering stage), and 0.4 kg/10a from 75 to 90 days after burial (flowering stage to ear emergence stage) for the 2012 and 2013 seedings, and 0.92-1.51 kg/10a from 75 to 75 days after burial for the 2013 seeding. Nitrogen leaching increased after the internode elongation stage, ranging from 1.90 to 1.93 kg/10a from 75 to 90 days after burial (around the flowering stage to 17 to 21 days after ear emergence).

In 2014, the amount of nitrogen leaching increased after the leaf stop extraction stage.

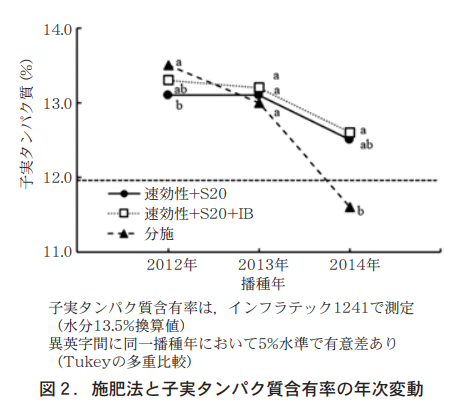

2. growth, yield, and quality of "rah-rah barley" by labor-saving fertilization

Growth, yield, and quality by fertilizer application method are shown in Table 2. Compared to the partial application, the number of stems and ears tended to be lower in the fast-acting fertilizer and S20 blends, especially in the 2014 seeding, and the ear emergence and maturity stages were almost on the same day. Stem and ear numbers were similar for the fast-acting fertilizer and S20 and IB blends, with the same ear emergence date and maturity date delayed by about 1 day. There was no difference in the degree of downfall between the test sites. The yields of the two fertilizer-saving treatments were similar in 2012 and 2014 sowing and higher in 2013 sowing, and there was no difference in quality. Seedling protein content was above 121 TP3T in the labor-saving fertilizer treatments in all three years tested, including the 2014 sowing, when the protein content was below 121 TP3T in the partial fertilizer treatment (Figure 2).

Consideration

A labor-saving fertilizer application system for Chinese noodle wheat "Ra-mugi" was studied, in which a combination of a fast-acting fertilizer and a controlled-release fertilizer is applied during the off-planting period, and ear fertilizer and fertilizer application at the ear-planting period are omitted.

First, we investigated the nitrogen leaching rate of S20 fertilizer by time period. The nitrogen leaching rate of S20 varied from 0.37 to 1.51 kg/10a and from 1.39 to 2.17 kg/10a (Fig. 1) for the period from 45 to 60 days after burial (during the internode elongation period to leaf stop extraction) and from 60 to 75 days after burial (during the leaf stop extraction period to flowering period), respectively, and the leaching rate for the period from 1.39 to 2.17 kg/10a (Fig. 1) for each of the three years. The amount of nitrogen leached from the leaf-extraction stage to the flowering stage was lower in the 2014 seeding than in the other two years.

Since nitrogen leaching of S20 is temperature-dependent, the average temperatures after mid-March, when differences in leaching occurred, were 1.2-1.4°C higher than normal for the 2012 sowing, 1.2-2.2°C higher for the 2013 sowing, and 0.4-1.7°C higher for the 2014 sowing in mid- and late March, respectively, and 2.2°C higher for the 2012 sowing and 0.4°C lower for the 2013 and 2014 sowing in early April. In early April, the 2012 seeding was 2.2°C higher and the 2013 and 2014 seedings were 0.4°C lower than the 2012 seeding (Yukibashi AMeDAS). Therefore, factors other than the average temperature may have contributed to the delayed nitrogen leaching in the 2014 seeding.

Kobayashi et al. (1997) reported that a certain amount of water penetration into the coating membrane is necessary for nitrogen leaching of coated fertilizer to start. The delay in nitrogen leaching in the 2014 seeding may be due to low precipitation in February, which resulted in insufficient water penetration into the coating and delayed leaching.

According to Fukuoka Prefecture's fertilizer standard, the timing of ear fertilizer application in a divided application is the stalk-planting period, and the amount of nitrogen applied is 2 kg/10 a. The cumulative nitrogen leaching of S20 reaches 2 kg/10 a, which is equivalent to the amount of nitrogen in the divided application of ear fertilizer, from the leaf-extraction period to the blooming period, which is later than the stalk-planting period. Therefore, it was necessary to clarify the effects of nitrogen fertilization around the leaf-extraction stage on nitrogen content, yield, and quality of wheat in order to examine the effects of S20 as an ear fertilizer. Although data are omitted due to space limitation, when the ear fertilizer was applied at the stem-rotation stage or at the leaf-extraction stage, the nitrogen utilization rate was about 701 TP3T at both stages, and no significant differences were observed in the number of ears, seedling weight, and protein content of the seedlings.

Ishimaru et al. (2016) reported that when ear fertilizer was applied at the stem-standing stage, fertilizer nitrogen utilization was as high as about 701 TP3T, similar to that of fertilizer applied at the ear-justification stage. Therefore, it was considered that the nitrogen absorption capacity of wheat was as high when the ear fertilizer was applied at the stop-leaf extraction stage as it was at the stem-standing and ear-planting stages, and no difference was observed. Therefore, S20, which is applied during the tillering stage and nitrogen is leached from around the leaf extraction stage, seems to be as effective as a fast-acting nitrogen fertilizer for ear fertilization during the stem-rotation stage.

Next, to examine the type and amount of fertilizer with regulated fertilizer efficacy that should be added in the labor-saving fertilization method, two types of fertilizers were applied: a combination of 3 kg/10a of fast-acting nitrogen fertilizer and 9 kg/10a of S20 or a combination of 3 kg/10a of fast-acting nitrogen fertilizer, 8 kg/10a of S20, and 1 kg/10a of IB, and the effects on growth, yield, and fruit and protein The effects on growth, yield, and seedling protein content were compared with those of conventional fertilizer application (Table 2, Figure 1). Generally, the nitrogen leaching rate of controlled-release fertilizers is 80-901 TP3T of the fertilizer applied. The amount of nitrogen fertilizer was increased by 2 kg/10a to 7 kg/10a.

The results showed that the number of stems and ears of fast-acting fertilizer and S20 tended to be lower than those of the fractional application, suggesting that S20 does not leach nitrogen until the stem-planting stage after application, resulting in insufficient nitrogen supply. On the other hand, there was no difference in the number of stems and ears among the fast-acting fertilizer, S20, and IB (Fujiwara et al. 1998), because IB is a fertilizer that changes to urea through hydrolysis (Fujiwara et al. 1998), and rainfall after application causes hydrolysis of the nitrogen from IB and provides a continuous nitrogen supply. In all three years tested, rainfall occurred immediately after fertilizer application, and this may have initiated the supply of nitrogen from IB, compensating for the reduced nitrogen from the fast-acting fertilizer and ensuring the same number of stems and ears as with a partial fertilizer application.

Therefore, fast-acting fertilizers and S20 and IB blends are preferable to ensure a stable nitrogen supply, stem number, and ear number. The thousand-grain weight, volume weight, yield, and test grade did not differ from the conventional application of any of the compound fertilizers (Table 2). Seedling protein content was above 121 TP3T in all three years tested (Figure 2).

The above results indicate that when Chinese noodle wheat "Ra-Mugi" was sown at the right time and fertilized with a combination of 3 kg/10 a of fast-acting nitrogen fertilizer, 8 kg/10 a of S20, and 1 kg/10 a of IB during the seedling stage, the growth, yield, and seedling protein content were equivalent to those of conventional fertilizer application, and that labor-saving fertilizer application was possible without using ear fertilizer or fertilizer at the ear-planting stage. Labor-saving fertilizer application was possible by omitting the application of ear fertilizer and early-season fertilizer.

References

●藤原俊六郎・安西徹郎・小川吉雄・加藤哲郎編 1998.

土壌肥料用語事典.農文協.東京.216−217.

●古庄雅彦・馬場孝秀・宮崎真行・石丸知道・大野礼成・髙田衣子・浜地勇次 2013.

日本初のラーメン用小麦品種「ちくしW2号」の開発と高品質生産技術の確立.

日作紀 81 (別号1):518−521.

●石丸知道・荒木雅登・荒木卓哉・山本富三 2016.

中華めん用小麦品種「ちくしW2号」の子実タンパク質含有率における施肥窒素の利用率と地力窒素の寄与率.日作紀 85:385−390.

●小林新・藤澤英司・羽生友治 1997.

被覆肥料の溶出と被覆膜内外の水分の挙動.土肥誌 68:14−22.

●田中浩平 2013.

現場が求める技術開発−硬質小麦「ちくしW2号」(ラー麦)普及の取り組みから−.

日作九支報 79:65−68.

No Soil - No. 15

化学肥料だけしか使わない畑のコムギの生育

−堆肥だけの畑と比べる−

Jcam Agri Co.

北海道支店 技術顧問

松中 照夫

化学肥料を世界で最初に市販したのは,イギリスのローズだった。1843年7月1日のことである。それまでの作物の養分源はもっぱら堆肥であった。ドイツのテーヤが指摘した植物の養分は土にある有機物(フムス=腐植)であるというのが通説の時代だったからである。

1. an era in which plant nutrients are changing from organic to inorganic

In 1828, Sprengel of Germany was the first to question this common theory and point out that plant nutrients are not organic but inorganic (minerals). It was Liebig, also of Germany, who further supported his point of view and popularized the theory in 1840. It was during this period that Rose marketed an inorganic chemical fertilizer (a patented fertilizer composed of lime superphosphate, ammonium phosphate, and potassium silicate) as a nutrient for crops.

Rose attempted several trials in his hometown of Rothamsted, Harpenden, to verify the efficacy of the chemical fertilizers he intended to sell. He conducted pot trials in 1837-39 and small field trials in 1840-41. From these trials, he recognized the importance of phosphorus as a nutrient for cabbage, since the highest yields were obtained when cabbage was treated with ammonium phosphate, which contained phosphorus as well as nitrogen.

2. overview of broadbore wheat field trials

Rose brought in Gilbert, who had studied chemistry at Liebig's, as a scientific collaborator and began comparing the nutrient effects of chemical fertilizers and compost. It was in the fall of 1843, the very same year that chemical fertilizers were introduced to the world, that he sowed wheat (fall-sown wheat) as a crop for testing. This is the Broadbark wheat test plot introduced this month. The year 1843 was the founding year of the Rothamsted Agricultural Experiment Station.

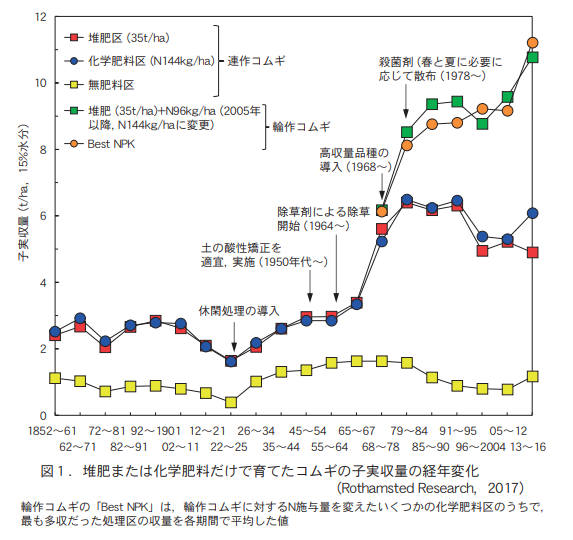

This field trial has continued uninterruptedly since then until now, 179 years later. In addition to the no-fertilizer treatment, the chemical fertilizer-treated area was given a certain amount of phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and other nutrients in addition to nitrogen at four levels: 0, 48, 96, and 144 kg/ha of nitrogen. Currently, in addition to these four levels, trials are continuing at seven levels, including treatments of 192, 240, and 288 kg/ha. Of course, since the trials were started in the same year that chemical fertilizers were introduced to the market, there is no field on earth that has been grown with chemical fertilizers alone for a longer period of time than the Broadbork field.

1968年には,試験に用いるコムギの品種を高収量品種(稈長を短くして多肥条件でも倒伏しにくくし,葉を直立にして受光態勢を改良した品種)に変更している。同じ1968年からそれまでの連作処理の他に5年輪作の処理を加え,堆肥35t/haに窒素を96kg/ha(2005年からは144kg/haに増量)追加する処理もおこなうようになった。

3. results of broadbark wheat field trials

1) Yield equivalent to composted area with appropriate amount of chemical fertilizer

Figure 1 shows the results of this trial. The yield of wheat seedlings in the chemical fertilizer (N144 kg/ha) area of the continuous wheat test was not much different from that in the compost area. It was confirmed that the production of wheat seedlings with chemical fertilizer alone was almost equal to that with 35 t/ha of compost, if the amount of fertilizer applied was appropriate.

Interestingly, after 60 years of continuous cropping, in 1902, both treatments showed continuous crop failure and yield decreased. When the fallow treatment was introduced (one-year fallow followed by four-year row cropping), yields recovered again. This indicates that the continuous cropping failure of wheat occurs not only in the chemical fertilizer area but also in the compost area, and that the fallow treatment is more effective for recovery than the nutrient treatments such as compost or chemical fertilizer.

(2) Dramatic increase in yields with the introduction of high-yielding varieties

Since 1968, when high-yielding varieties were introduced, the yield of row crops of wheat has nearly doubled, despite no change in compost or chemical fertilizer application treatments. This confirms the high seed production capacity of high-yielding varieties.

Furthermore, in the five-year crop rotation established after 1968, when the nitrogen content of chemical fertilizers was added to the compost to increase the total nitrogen application, the yield was nearly 10 t/ha. This is not only about three times the yield of the composted area in the old variety era until 1967, but also about twice the average yield in Japan. The effect of the addition of chemical fertilizer nutrients to the compost is clear, and the high-yielding variety's response to fertilizer nutrients is understandable.

3) Soil organisms in fields where only chemical fertilizers are used.

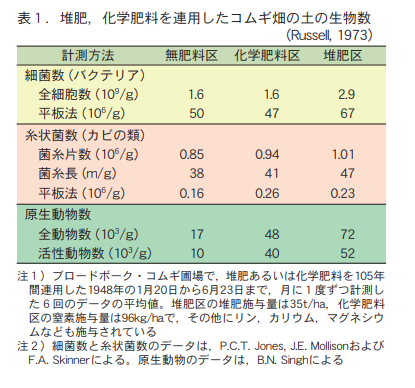

Some people worry that continued use of chemical fertilizers will kill off the organisms in the soil and "kill the soil. If the continued use of chemical fertilizers were causing the extinction of soil organisms, it would, of course, affect the yield and growth of the wheat crop in this trial. However, such a phenomenon has not been observed at all, even in this Broadbark wheat test plot, which is the longest in the world where only chemical fertilizers have been used (Figure 1). Soil in the chemical fertilizer and composted manure plots

According to the results of the biological counts, there is no evidence that the continuous application of chemical fertilizers alone has resulted in the loss of soil organisms (Table 1).

Russell, who was the head of the Rothamsted Farm Experiment Station for many years, clearly pointed out that "there is some concern that chemical fertilizers are harmful to earthworms and should not be used. However, Russell clearly pointed out that "there is no indication that this is the case in the Broadbark wheat test plots after more than 100 years of continuous application of chemical fertilizers in amounts greater than customary" (Russell, 1957).

These test results indicate that, as long as chemical fertilizers are used appropriately, there is no need to worry about their negative effects on crops.